Authors:

(1) Nir Chemaya, University of California, Santa Barbara and (e-mail: nir@ucsb.edu);

(2) Daniel Martin, University of California, Santa Barbara and Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University and (e-mail: danielmartin@ucsb.edu).

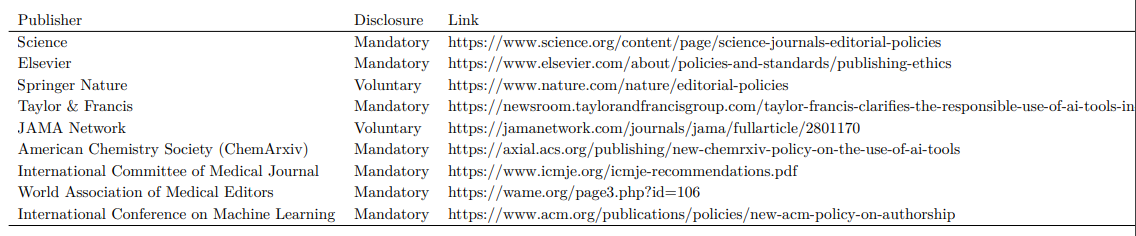

Table of Links

- Abstract and Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- References

- Appendix for Perceptions and Detection of AI Use in Manuscript Preparation for Academic Journals

Appendix for Perceptions and Detection of AI Use in Manuscript Preparation for Academic Journals

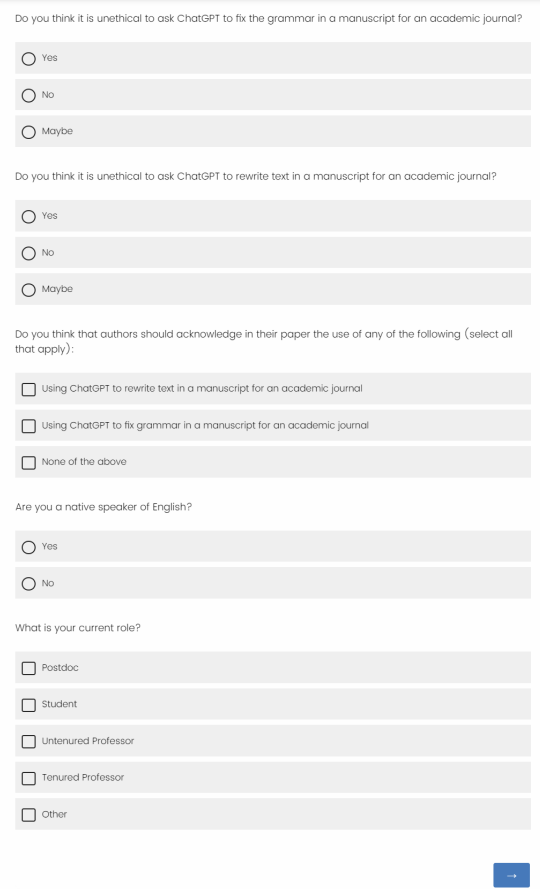

A Survey Screenshots

B Additional Tables

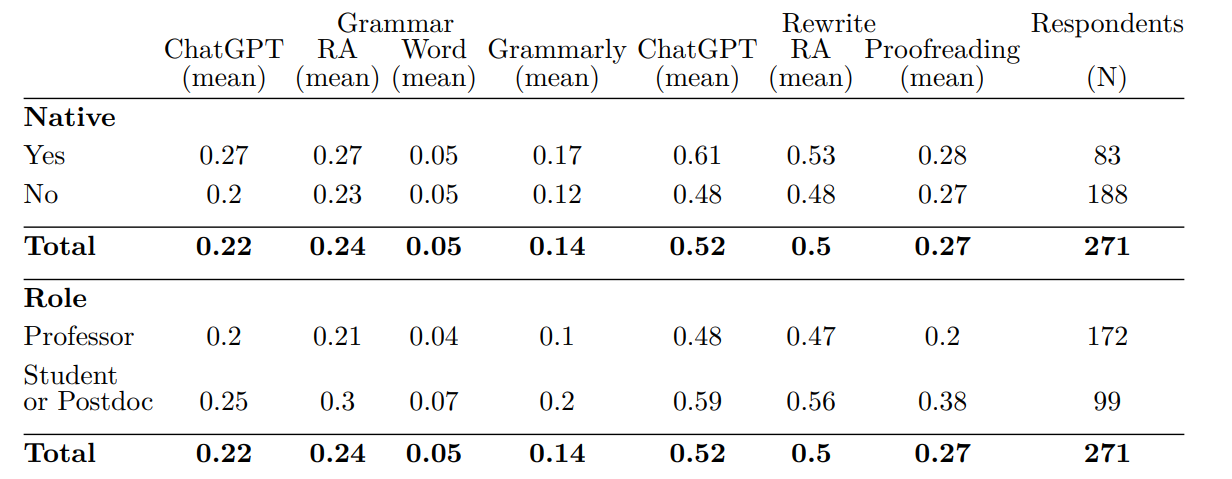

Table 3 provides summary statistics for whether authors should acknowledge different forms of assistance. The top panel provides the average responses broken out by being a native English speaker or not, and the bottom panel by being a professor or not.

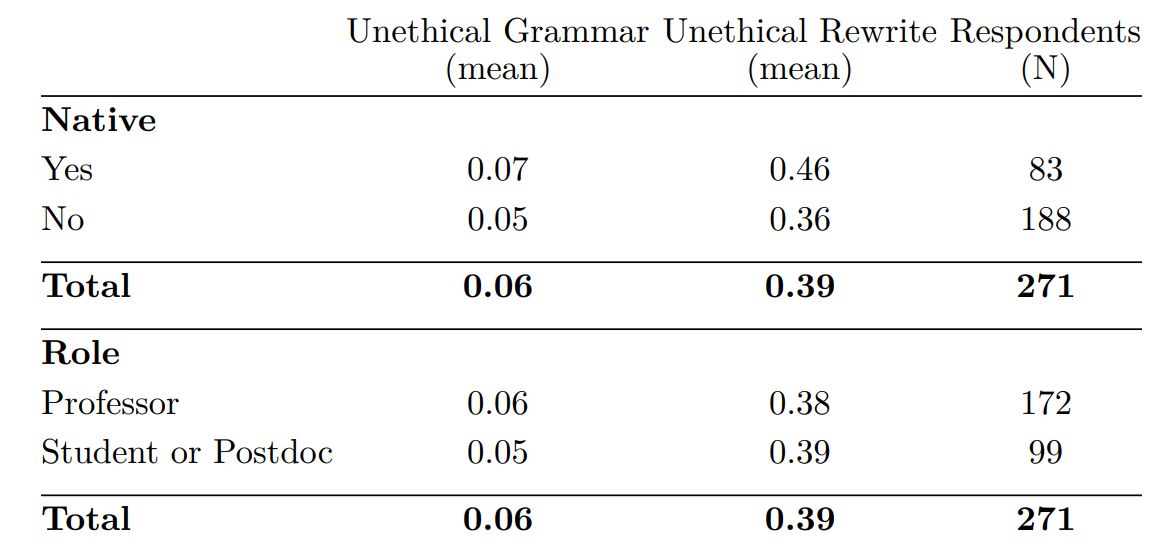

Table 4 shows the results of asking if it is unethical to use ChatGPT to correct the grammar or rewrite the text in a manuscript for an academic journal. For fixing grammar, there is a consensus that it is ethical to use ChatGPT, with 94% of the researchers replying that it is not unethical. However, for rewriting, this becomes more open questions with only 61% respondents thinking that is not unethical. We allow respondents to answer “maybe” to these questions to identify which researchers are uncertain about this question. However, in our analysis, we categorize respondents into those who believe it is ethical and those who either answered that it is unethical or indicate that it is “maybe” unethical.

When we compare native English speakers to non-native ones, we find that there is not a significant difference in perceptions of ethics around fixing grammar: 7% compared to 5% (twosample test of proportions yields p=0.211). However, when it comes to rewriting text, 46% of native English speakers think that it is unethical to use ChatGPT, compared to 36% of non-native speakers. A two-sample test of proportions yields p = 0.121 on a two-tailed test or p = 0.060 on the one-tailed. When we compare professors to students and postdocs, we do not find any significant difference for either fixing grammar and rewriting text (for grammar p=0.76 and for rewrite p=0.977).

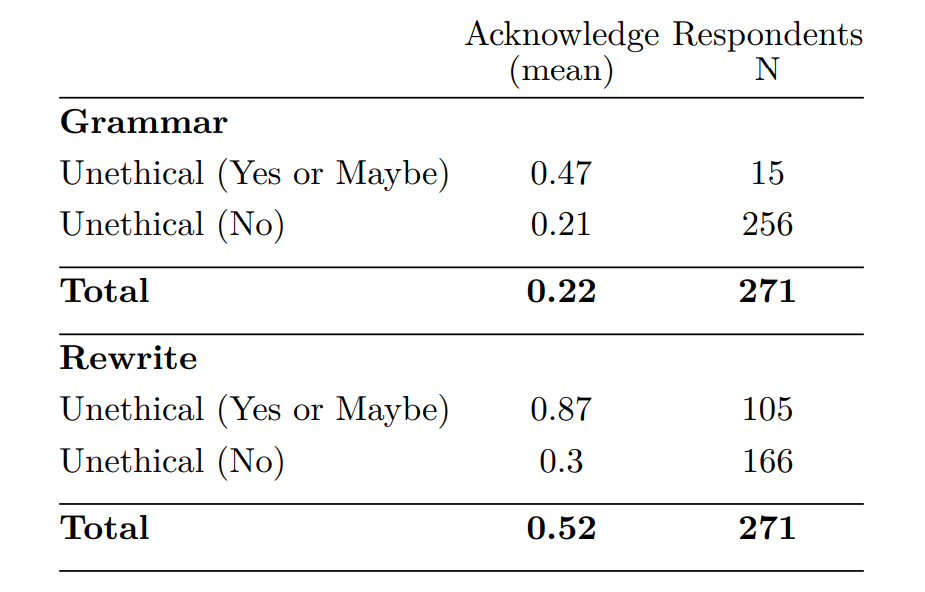

Finally, Table 5 shows the perceptions of respondents regarding whether one should report the use of the ChatGPT for assistance in manuscript preparation. This includes those who consider it ethical to use it and those who believe it to be unethical or are unsure (answered “maybe”). A significant difference exists among these groups. When researchers perceive it as ethical to use ChatGPT, only 21% (30%) believe that reporting is necessary when using it for grammar correction (rewriting). In contrast, researchers who view it as unethical or are uncertain about its ethics have a higher percentage, with 47% (87%) believing that reporting is necessary. This difference among the groups is significant. A two-sample test of proportions yields p=0.017 (0.0001).

This paper is available on arxiv under CC 4.0 license.